Growing up in the digital age is by no means a problem in and of itself. Before social media, the internet was bustling with people and teeming with information. As the internet started to take hold in many homes, there was the always-looming idea of "you never know who somebody really is on the internet," the idea that over-sharing will lead to drastic or dire consequences. Internet handles, usernames, and avatars were commonplace across the world as a means to mask personal identity but give a voice on the internet. Message boards, forums, and even personal websites and journals were mainstays of the internet, all of them early or precursory forms of "social media" before social media. Everything was going well... until the social media nation attacked. Early social media such as Friendster and Classmates and SixDegrees started to spring up seemingly overnight at the turn of the century. Rather than solely adopting our online personas, hidden behind our (cringeworthy, adolescent) usernames, users now made profiles around their own personal information and linked their accounts or added friends. Connections were made, people rejoiced at this newfangled way to either get or keep in touch with others that may or have left our immediate lives (for better or worse).

But as the essay "Accumulating Affect" makes a startlingly scary point in how we have developed as a worldwide culture in the digital age. The essay notes, "Sites such as Facebook would not exist if they did not reproduce sociability... Social Networks are virtual spaces driven by the active participation of users" (236-7). Now more than ever, everyone is sharing everything they think, see, or do in every way possible. From text posts on Facebook to pictures on Snapchat or Instagram or videos on Vine and Youtube, everything that everyone experiences in the digital age makes its way into the hands of nearly infinite amounts of shares, likes, retweets, etc. Author Jennifer Pybus notes that "when a user places something into the archive, he or she is uploading an object that has social, and hence affective, value. The object in question has the potential to affect as it moves between the user and the larger network of friends... Thus affect accumulates, sediments, and provides additional cultural significance to that which gets circulated" (240). As such, sharing is inherently a good thing in terms of sociability; the material or experience has the ability to connect the person sharing with any and all who receive or interact with the shared material in some way. In this way, the more we share our experiences, the more "sociable" we make ourselves seem. But seem is the operant word here; does sharing our experiences (or lack of sharing) really make us any more or less sociable in comparison to our worlds "offline"?

Just because a plethora of Facebook friends "like" that one picture of the burrito you took last weekend to show that you are such a #foodie doesn't necessarily make you any more inherently sociable, does it? Pybus notes that "people do not log in to social networks to live anonymous lives, but instead to live what Zhao and colleagues refer to as 'nonymous' or (semi)public lives" (243). We, as a culture, use social media as a tool or means to connect with one another in a way that doesn't necessitate having to have a close, personal relationship with one another. Simply just being friends with someone on Facebook is the modern equivalent of being an acquaintance with someone without necessarily having to invest time or energy into cultivating long-lasting friendships with said people. The term "Facebook friends" actually has this distinct meaning that has developed out of this symbiotic, affective relationship, a meaning that is widespread and well understood. Pybus notes that "each time we upload something about ourselves, an intention or desire motivates us to do so" (242). We want to express ourselves publicly, make ourselves a spectacle of affection or inspection. We want people to see us, see what we're doing, know what we're thinking, even if it isn't necessarily relevant to anyone but ourselves (really, Dave, nobody else cares if you're thinking of buying a new set of window curtains. Honestly).

Richard Pryll's "Lies" seems an interesting take on the boundry between private and public, truth and lies, fact and fiction. Each path one takes provides a different context for the information provided. In each version, Antoine and Gabriella are two different "people." When following just "Lies," one is told that Antoine and Gabriella are just journals, "meant for fantasizing about sex in our journals," and that writing in the journals is "cheating" on one another. Yet when one reads just the "Truth" path, one is set to believe that the two main characters are, in fact, cheating on one another but are choosing to come clean about it (and therein forgive one another for their infidelity). If one alternates between truth and lies, it muddles this story up a bit. One might learn early on that the "lover" is a journal, one might not; with or without this context, later information becomes much harder to decipher as "reality" or in the journal. Knowing that it is a journal, the information becomes easier to perceive as its "cheating," when in reality it isn't (and the reader would know this if they know about the journal). By using phrases and words with deceptive meaning, the author shows just how easy and simple it is to deceive the reader that might not have the proper context. The same lies in our perceptions of ourselves and others in the real world and on the internet. We often "adopt" a different persona, different set of personality traits when we're on the internet. We might be more or less inclined to share information, or even share different types of information, when we know that someone connected with you is reading or seeing it whereas we might be a little more lax when our anonymity cannot be questioned or lifted.

Just like in the main character's journals, we allow ourselves to be "ourselves," or more less like ourselves, when in the company of or in presentation toward others. This persona we develop may be more or less characteristic of who we truly are. An introvert may be more likely to "come out of their shell" when outside of the physical company of others, even if they're within the "digital" company of others. In reverse, an extrovert may feel themselves "confined" to a simple space such as a blog or social media, unable to fully or openly express themselves. A physical audience or presence is intimidating to many who aren't entirely introverted as well. By "limiting" that audience to a digital presence, one has the ability to reach millions upon millions of other people nearly instantaneously but isn't subjected to physical scrutiny or judgment. Anonymity and/or lack of physical presence allows for a broader range of characteristics to be displayed, acknowledged, or bolstered. Such is the reason that social media platforms such as Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, Instagram, etc. allow those who want to have a voice and audience to use it vastly, but those that want to remain "nonymous" and otherwise be a wallflower are able to do so just as well.

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Monday, April 11, 2016

Personality Pays

“The digital archive can therefore illuminate how the

conflation of economic and social relations is not simply an alienated process

but always already engaged and active.”

Jennifer Pybus’s chapter entitled “Accumulating Affect:

Social Networks and their Archives of Feelings” takes a more in-depth look at

how users of social media create an affect for themselves through these

platforms that engage user emotions. She asserts that archives not only

preserve knowledge but also the emotions of that particular moment something is

posted.

Because of this, we are able to reflect on our posts, seeing

where we were emotionally at a given point in time. Our previous engagements

with social media can even shape and transform the way we feel in the present.

Whether we like it or not, social media has transformed the

way we view the world, and, yes, it has changed the way the world views those

who participate online. As Pybus mentions in her work, it isn’t just private

citizens that are reaping the benefits of an online presence. Both small and

big companies as well as public figures, like musicians and politicians, have

recognized the potential that social media provides to market themselves.

I currently work in a tourism department for a city in

Illinois, and one of my jobs is to keep an updated record of all the businesses

within the city, and, trust me, it’s hard to market a business without an

online presence. I’ve always thought that if companies don’t have at least a

Facebook page, they probably either already have a decent customer base and don't care or

they’re just honestly missing out on major marketing opportunities.

However, businesses and public figures aren’t the only ones

profiting from the economic value of social media digital archives. While it’s

true that social media platforms provide online spaces for individuals and

companies to record and reflect on memories and the feelings they evoke, some

have figured out another way to profit from social media.

After reading through Pybus’s work, I began to think more

about how individuals join in this “ongoing process of choice and curating the

self” through social media, creating the online affect that she focuses on in

the chapter. As a student with a concentration in composition and rhetoric, I

asked myself, who is the audience for all of this? What purpose does it serve?

It seems that as individuals, we create this affect mostly for ourselves

and those we know who are also on these sites. As Pybus suggests, we as

individuals engage in social media to archive moments, thoughts, and feelings

and to reflect on those later, continuously shaping our affects both on and

offline. In contrast, companies and businesses use social media to promote their

goods/services, reaching a wider (online) audience of potential paying

customers.

However, I do think there is a category of those using

social media, also for a solid purpose, that Pybus seems to overlook: what about

individuals that create an affect online for economic purposes? Sure, celebrities

create their affects on social media to promote whatever it is that they do to

make money—buy my album, go see my movie, come watch me perform stand-up

comedy. Yet, some individuals—NOT celebrities or well known prior to social media—have

capitalized on social media’s economic value by simply promoting themselves and their personalities.

This came as a shock to me at first, but, yes, normal

individuals like you and me are making money because of the online affect they

have and continue to create. One of the prime examples of this phenomenon is

Jenna Mabry, better known as Jenna Marbles.

While some may have made a name for themselves with a

certain post or video (who else remembers the Chocolate Rain guy?), it seems these moments are often short-lived. Jenna, along

with many others following her lead, has transformed the online world, bridging the gap between individual and business purposes for doing so. Her

tweets and YouTube videos have gained her thousands of followers within the

past few years—and she’s making a living of off it!

The affect that she has accumulated online has pushed

her closer toward celebrity status, but unlike most other celebrities, she

isn’t trying to sell you anything but her personality. Her display of “highly

performative subjectivities” that Pybus discusses has attracted people across

the globe. The affect that she has created has proved extremely relatable and

popular, transforming her into an online superstar.

Other online personalities have also thrived and made their living

through their affects created via social media, but I have to admit, Jenna is

one of my personal favorites. It does seem a little discouraging that most

of us on social media won’t ever gain the online notoriety that is required to

make a living out of the deal, but it’s interesting to think that it's now an

option. Welcome to the 21st century, right?

Hypertextual Lies Shall Set You Free!

Lies

raises

as many questions as longer works due to its hypertextual format, which seduces

the reader (or maybe not) into several careful readings, a task that is less taxing

with this work as compared to traditional works of fiction.

Fantasy is so much more interesting than the raw

reality of our day-to-day lives, and Pryll shows how lies emerge as a more interesting

version of honesty, as long as we are aware of the truth which our lies hide

and why we are compelled to fictionalize our experiences in the first place.

In my first run-through of Lies, I, like McKenzie, chose “Truth” the whole way through, only

to finish with an anticlimactic ending that lacked substance. Choosing “Lies”

throughout my second reading revealed more depth, especially with the addition

of metaphorical interpretations of “summer lovers” and the notion and act of

infidelity:

There are other codes

too. "Summer lover" is actually the names we call our journals. It

started when she and I started writing letters to each other. When [we] were writing to each other, we were

spending time together. When we were writing in our journals, we were

"cheating" on each other. "Sleeping with" our summer lovers

meant fantasizing about sex in our journals. She was the first to give her

journal human characteristics.

This false account is not only more interesting than

the truth, but it also has no conflict, which flies in the face of the

traditional requirement of a story needing strife to be considered a story; the

infidelities become symbolized both as acts of writing to oneself as opposed to

writing to a lover, coupled with the fantasy of one for the other—all desires

are fulfilled through artistic deception.

Erratically navigating Lies—Truth, Lies, Lies, Truth, for ex.—reveals subtle diversions

and additional details in the story, making it more engaging. The Lies always

spice up the story in interesting ways, such as in the following passage—a lie

that draws attention to the necessity of imaginative deception in writing:

Actually, this never happened. I am a writer,

and I wrote a story about an artist colony where this woman, who's craft is

inspiration, guides all the painters, writers, sculptors and poets to different

places in the city. Her favorite places are the bus depot and the subway

tunnels at night. She helps to expand people's minds with her beauty and her

mystique.

In the above passage, further

details

of scenery mentioned in other combinative selections of Truth and Lies are

given, only they are revealed to be the product of the writer’s imagination.

Pryll breaks the fourth wall and places other clues in the story that directly

let the reader know he/she is being manipulated, his “diorama” constantly

shifting before our eyes in a manner that is either engaging and game-like,

frustratingly facile, or somewhere in between.

Social Media Isn't All Bad

Jennifer

Pybus examines the benefits of social media in her article “Accumulating

Affect: Social Networks and Their Archives of Feelings.” She highlights the fact that “posting content

has become a necessary means by which to maintain intimacy with peers” for many

social media users (235). The archive of digital information is exponentially

expanding, even though privacy-protecting behaviors continue to increase,

especially among young people. Pybus analyzes the effects that the increasing

archive of digital information has on its users and the economy.

Pybus

begins by examining the social relationships found through social media. These

networks “allow users to: (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within

a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a

connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made

by others within the system” (Pybus 237). It’s interesting to note that Pybus

argues that “users don’t typically go to these sites to meet strangers, but to

maintain preexisting offline friendships” (237). That may depend on the type of

social media one looks at, because plenty of networks allow for anonymity and

to further the goal of creating new online friendships (think Tumblr).

Regardless of the anonymity of the user, social media does help people feel

comforted and built up when they are feeling insecure. This latter reason may

explain why so many details of a user’s life are fudged online. By posting only

positive or “airbrushed” experience to social media, users can feel more secure

due to the positive feedback they get from their friends list. Social media

promotes these interactions and, in doing so, becomes a successful example of

“stickness,” a term marketers use to refer to the “amount of time spend on a

website” (Pybus 237). The more time users spend on the network, the more

successful the network is.

While many

scholars argue that social media is used to exploit users into providing data

for the “information economy,” Pybus argues that users can “nonetheless enjoy

the effects of networked sociality generated when the engage with their

divergent groups of friends” through an “archive of feelings” (238). An archive

is not a static construct of documents, but rather an ever-changing ”space of

interpretation and contestation that has the power to make meaning through its

ability to privilege certain discourses over others. Who and what gets

remembered and who gets to make these existential decisions, are issues with

important social, political, and economic ramifications” (Pybus 239). In an

“archive of feelings,” focus is placed on how the texts are constructed, rather

than the content themselves. The creation of the archive preserves emotions and

memories, and these preservations can often be more important to the users than

what is actually created.

Social

media promotes a different way for bodies to connect with each other. In this

connection, “each message, note, and photo that gets uploaded carries with it

the ability to affect not only a friend in the network but equally the

individual user, based on the way that this object is received by the members

of his or her respective community” (Pybus 240). A piece of information’s

effect on a person changes based on whether he or she chooses to upload it to

social media to share with friends. The user uploads this piece for a reason,

and it has the ability to maintain relationship and memories through the act of

being shared with friends. The act of sharing allows people to feel connected

with each other and, in the process, encourages more sharing of information

with each other. As Pybus notes, “The more we use sites such as Facebook, the

more we post, the more we are motivated to generate and share additional

content” (242). The fact that social media is almost purely user-generated in

fact allows its continuation.

Of course,

Pybus highlights a paradox within this system because what is shared is only a

representation. Social media can never fully recreate experiences, regardless

of users’ desires to “place everything in the archive” (Pybus 242). However,

Pybus argues that “Such an archive would not only be utopian and perhaps

somewhat perverse, it would have the effect of erasing memory all together”

(242). Social media works because users make their own choices about what to

upload into the digital archive and what kind of experiences they want to

create within the network.

Because

users can create their own selves within social media, many scholars, such as

Sherry Turkle, conceptualize identity as having separate selves within each

network. We have different identities based on who we are talking to and

sharing with. Others argue that the different selves come “together to produce

a more singular, albeit fractured, identity, driven not only by the architecture

of the technology but also by an active need for sociality (Pybus 243). Regardless

of the theory one might subscribe to, users have the ability to present

distinctly separate selves to different groups of people, and, as Pybus argues,

it is important “to think about [the] related power/knowledge questions that

emerge when we begin to examine the choices that determine what information

will come to represent us, affect others, and subsequently affect ourselves”

(243).

Finally,

Pybus does attend to the fact that marketers are making increasingly

substantial use out of the data from social media. Why make a study of human

behavior and consumption when it is immediately available already on social

media? Concerns about how organizations are becoming “hungrier and hungrier” for

user data are not unjustified (Pybus 245). Pybus argues, however, that “To

focus only on how corporations extrapolate our data negates those very real

affective relations that propel the increased production and circulation of

data by users” (245). Social media users are still getting very important

benefits from the networks, regardless of how those ensuing relationships are

being analyzed.

Things are Confusing when Truth is Mixed in With Lies

Richard L. Pryll has managed to capture the essence of what it means to lie and tell the truth within his HyperFiction Lies. I feel I can make this claim as someone who decided to be sporadic in the reading. On my first go, I continuously would choose what I felt was best to read based on what he wrote. I’d read what would come up on the screen, look at it and process it for a few moments, and then decide whether or not I would want a truth or a lie. By doing it this way, I felt that I was going to give myself the best story. In the end though, I found I had given myself a headache and a lot of questions.

This is why I feel he was able to completely capture the moment of lying or telling the truth. Within each click, the reader is choosing what they want to hear, regardless of whether or not it is something they truly wanted. I found that mixing lies in with the truth, I was constantly trying to remember which actions I chose to do and what led me to where I was at in the story. Which seems to be the case in how life really works. Every time someone makes a choice, whether it is to lie or tell the truth, the story of what they’re talking about moves forward. The narrative changes, and so does the speaker. In the end, the person is either caught in a former lie or ends up living their life with that lie. Same with the truth. In lying about some aspects and telling truth in the others, the person speaking will continuously have to try and remember what they said that was a lie or if they told the truth.

After this experience, I found myself going and back and just choosing truth for the entire story. Although this clear things up to an extent, I found myself rather bored with the story. With this way of telling and reading it, it made me question the extent of telling the truth again in real life. A lot of times, when someone tells a story, the truth may not always be important. When I speak about what I did with what my day, a lot of it will be mundane and boring. No one wants to hear about how I read this story over several times by myself in my room. They want something more exciting. It’s here where it should make the reader pause and wonder on the truth. How much of the truth do people need? How much truth are you fully getting when you speak to someone? This tends to be answered a bit by choosing all lies.

When choosing all lies, I found that many of the details of the truth story were not to be found. The main example I’m thinking of is how the writer of this piece had secret terms for things. Words such as “rum and cokes,” “dancing,” and “summer lovers” takes on a new perspective for the reader in the all lie section. However, I found myself questioning if these codes were true or not. Since if you choose the lie section all the way through, whose to say that any of what is being told is really true? A lie is fiction, made up, so who is to say that the narrator is not lying about these secret codes? If he was telling the truth within the lie section, then is the lie section really a lie? If he was lying about the secret codes, it makes things even more difficult for the reader. Just think about the fact that regardless of whether or not the secret codes he reveals are true, the perception changes if you go to read through the truth section again.

In regards to temporal play, it felt as though the story progressed in different ways. If the reader chooses to switch between lies and truths, than the narrative ends rather quickly. In the truth section, it slows down and time passes at a rational rate. With lies, it felt as though time was moving slower, and possibly that there were more things to read in the lie section. This could once again play to the reality of telling a truth, or a lie, or mixing it up. When I speak truthfully, everything tends to move at a normal rate, I’m not worried about judgement or being caught in a lie since what I’ve said is the truth. When I tell a lie, things move slower. I constantly try to make sure that I’m not caught in any of my fabrications. When mixing it up, I’m constantly worried about slipping up. Will one part of the story I lied about contradict with a truthful part I told? This play with truth and lies in a narrative help to move at the same pace as real life would.

Just Because You Can Create Hypertexts Doesn't Mean That You Should

Do

I write based on truth or lies? What if I create my own code words that only I

understand and make you, the reader, guess which code words are actually code

words and which ones are fake code words? And what happens if I create the blog

using hyperlinks, but those links are dead, broken?

I

could say that I really enjoyed Rick Pryll’s hypertext “Lies”; the opening

statement was proven by the story, that lies are really more interesting, and I

just couldn’t wait to see wait new and exciting events would pop up next. In

all honesty, I had high hopes for this hypertext. The “truths” version versus the

“lies” version was a clever gimmick. But it was written in 1992 and converted

for the web in 1994. I would have been very impressed with the hypertext

structure back then (yes, I had a computer and dial-up internet). But saying that

“I really enjoyed” it would be a lie. I found that the use of pronouns and

other ambiguities created more disjointedness between the hypertexts rather

than the fluidity that Pryll was striving for. Doug Bonnema’s analysis

of “Lies” also points out that Pryll’s story “is somewhat sophomoric.”

Bonnema does praise “Lies” as “an ideal introduction for students to the new

and multi-layered possibilities attainable through hypertext fiction.” I think

that is an overstatement; “Lies” is a basic example, but one that is easy to

recognize and use.

Ironically,

none of the links provided by Pryll on the “Lies” webpage to his interviews and

lists of other hypertexts work. So in an attempt to learn more, I started with

an equally basic Google search for “Rick Pryll Lies.” I found that Rick Pryll has struggled to maintain

a social media presence; again, odd for someone who touts himself as “an

award-winning author and poet, best known for his hyperfiction short story

“LIES” [. . .]. First published to the web in 1994, “LIES” has garnered praise

from the Wall Street Journal, SHIFT magazine, and several other publications in

print and online. It is cited in more than seven books, has been translated

into Spanish and Chinese, and continues to be featured on the curriculae at

several institutions of higher learning.” Pryll has two blog pages, neither of which

has been updated since 2014: Foolishness: the

life and times of Indie Author Rick Pryll and Rick Pryll’s LIES, the blog. His twitter

account @rickpryll is up-to-date, but Pryll retweets more than he posts

original comments. His biography on Twitter states that he is currently writing

and editing a middle grade novel, but no internet search resulted in any

additional information. I know that maintaining a social presence, a deliberate

maintaining, requires extra time and effort. I did my best to live tweet the

English Studies Conference last week #EIUESC16, but I was concerned that I

appeared rude during presentations when I was on my phone in a professional capacity.

I am always gleeful when someone outside my circle retweets or likes a tweet

because I know that my efforts have been successful. However, it seems that a person

who was an early user of a creative means for writing using programming/the

internet would recognize the impact of a social presence.

So

I wanted to experience more hyperfiction and preferably more creative

hyperfiction. One of the top results from my Google search was the webpage for

Kirkwood (Iowa) Community College faculty member Sue Kuennen’s New

Media Literature course. Again, a webpage in which the links are not all

up-to-date, but many were. I was intrigued by “Sunshine ’69” by Bobby Rabyd;

this hyperfiction allowed the reader to travel via multiple hypertexts—a calendar,

road map, suitcase, radio, and a bird. Some pages suffered from some poor

choices in graphic and text placement; I could not read the text that was

printed across the Summer ’69 banner. And even after downloading RealAudio

Player, I received an error message for every one of the “8-tack tapes.” Maybe

it was copyright issues, but if that was the problem, why not simply revamp the

site and make that statement? The problem that I had with this text was that I

could not find a solid plotline. I stumbled into a set of dialogue between two

male characters discussing how one was leaving for basic training followed by

Vietnam and how the other was planning to burn his draft card and go to prison

(yes, I felt like I was reading the script for Hair), but that conflict was not throughout the links.

While

I thought “Lies” was too simplistic, I found both “Sunshine ‘69” and “Cliff College: An Interactive Mystery” too

confusing because of their overwhelming number of links and overcomplicated

paths to travel through the links. I spent less time on “Cliff College” because

I was becoming frustrated; I wanted to solve the murder, but in all my clicking

and reading, I never found a murder to solve!

I

also wonder if writers/programmers/designers (I don’t know what to call the people

who created these works) lost interest years ago because the graphics are very

dated. Both “Sunshine ‘69” and “Cliff College” look like one generation past

the Oregon Trail computer game:

I

could not end my exploration without finding a hypertext that I could truthfully

say that I enjoyed, and I found it in Daniel

Merlin Goodbrey’s “Henry”. This hypertext appealed to me because it

combined a simplicity with more recent graphics, although the repetition of the

graphics and music does become annoying. Sue Kuennen suggests that Henry could

be categorized hyperpoetry, which might be why I was willing to accept the simplicity.

Like “Lies” the repetition of lines starts quickly, so by providing a limited

number of options the author does not complicate the text.

Truth—I

found the puzzle (or puzzles) with S.

more interesting and more enjoyable than the hypertexts. I can see the allure

of writing in such a way, but I don’t think any of these creators have found a viable

combination of text and hyperlinks/internet/programming to produce a work that

withstands literary scrutiny.

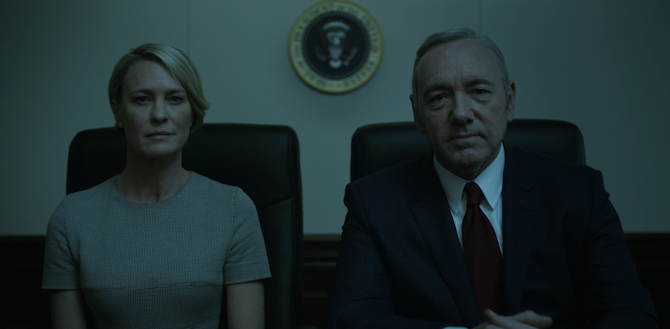

Manipulating Digital Spaces in House of Cards S.4

In

Jennifer Pybus’s article, “Accumulating Affect: Social Networks and Their

Archives of Feelings,” the role of social media in society is questioned. Pybus divides those who are actively engaged

in social media into two camps. The

first being digital natives, or those who see “new technologies…as the primary

mediators of human-to-human connections” (235).

These are the younger users who have only ever experienced a world in

which digital media exists. For these

users, posting content is a necessary means by which to communicate with

peers. In this group, those who do not

actively participate are at risk of social isolation. The secondary group, or digital immigrants,

are those people who have slowly moved into the digital realm. This group’s demographic is made up of older

users who are more concerned about the visibility of their personal information

than the digital natives. In order to

remain relevant, digital natives must remain visible and current within their

network of friends and continually circulate user generated content. This

system creates a culture of disclosure “predicated on a distinct set of

beliefs, norms, and affective practices that legitimate the constant uploading

of personal materials” (236). Our

relationship with digital media and the data that we produce has caused a

fundamental shift in the ways we express ourselves socially and have had a

significant impact on the ways in which advertisers market themselves to

us. This shift has trickled further on

into American politics and has affected how politicians reach out to different

voting populations, a shift that has been featured in Netflix hit series, House of Cards.

The

most recent season of House of Cards,

pits Frank Underwood against Will Conway, a young republican who has perfected

the art of self-marketing through the use of webcam broadcasts, Instagram,

search engine manipulation, and eventually, public access to his personal

phone. Although his age would put him in

the category of digital immigrant, his political campaign fits more in line

with the digital natives, or those who are younger and therefore live lives

that incorporate digital media to a further extent. Pybus says of the digital natives, “this

younger demographic is not as concerned about the visibility of their personal

information. Instead, they are more

apprehensive about their ability to control what they have chosen to circulate

online” (235). Conway expresses this by

making his personal life available for those who are interested in

watching. He posts video blogs of

himself and his family constantly, and when rumors begin to circulate about

him, he addresses the rumors directly to the public through the use of personal

videos. Conway relies heavily on his

media presence because he knows that voters respond well to it and that they

find him to be more honest and open. Of

course, this is not the case, as far as backdoor politics go, Conway is

incredibly skilled. He is right up there

with Frank Underwood as far as scheming and manipulation, and one could argue

that Conway is manipulative on a grander scale than Underwood because Conway

misrepresents himself to more people on a daily basis due to his expanded media

presence.

Conway

takes advantage of the general assumption made by Zhao in regards to the term

‘nonymous’. The claim is that “people do

not go to these spaces [digital media] to completely reinvent themselves but,

typically, to upload more truth than fiction” (243). Under this assumption, one would expect

Conway’s constant media presence to be truthful in nature rather than

manipulative; Conway’s online persona would be more in line with the truth

rather than a fabrication. Of course,

viewers of the show know this to be an absolute lie, his video archive and

seemingly open desire to be seen is a fabrication that allows Conway to pick

and choose the points at the forefront of his political campaign. Sunden says, “we write ourselves into being,”

but I would argue that we write our personas into being like Conway manages to

in House of Cards. Conway conceptualizes his digital profile as

an archive that allows him to spread disinformation. Pybus states that conceptualizing digital

profiles as an archive allows us to “determine what information will come to

represent us, affect others, and subsequently affect ourselves” (243). Conway’s tactical advantage stems from the

way he controls his personal information to propagate the lie that has essentially

turned into his public identity.

Although he wants people to believe that his public identity and his

personal identity are one in the same, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Frank

Underwood is less influential in terms of his digital archive and so he must

find other means in which to manipulate voters.

Like the advertisers, Frank must find a way to mine data from the social

media in order to stay ahead of his competitor Conway. Pybus states, “users are always creating

important opportunities for marketer, who intuitively understand that new

economic possibilities now reside in the generating of passionate interests, as

people increasingly come to express their intimacies publicly” (243). By mining this public expression and

manipulating media through the use of buzz words, Frank manages to stay ahead

of Conway.

Frank

has an advantage over Conway too in terms of assessing the public sphere, he

has full access to the NSA and therefore has the best monitoring capabilities

in the world. From his data he decides

to attack the public utilizing “sentiment analysis” or “opinion mining.” By staying on top of public opinion, Frank is

able to navigate his public persona in a way that showcases what the voters

want. Or more specifically, it allows

Frank to readjust the value placed on Claire, his wife. Because her public persona is held in such

high esteem, Frank attaches himself to her and together they become quite the

adversary for Conway.

Frank

has an advantage over Conway too in terms of assessing the public sphere, he

has full access to the NSA and therefore has the best monitoring capabilities

in the world. From his data he decides

to attack the public utilizing “sentiment analysis” or “opinion mining.” By staying on top of public opinion, Frank is

able to navigate his public persona in a way that showcases what the voters

want. Or more specifically, it allows

Frank to readjust the value placed on Claire, his wife. Because her public persona is held in such

high esteem, Frank attaches himself to her and together they become quite the

adversary for Conway.

House of Cards season

4 depicts how social media has not only changed the ways in which people relate

to one another, but also the ways in which politicians can take advantage of us

by creating falsified personas that people take for true representations. Although this essay focused on House of Cards, the truth of the matter

is that politicians are constantly catering their messages and online personas

in a way that is meant to manipulate.

From hashtag campaigns, public photo ops that emphasize our candidate’s

personable qualities, to twitter messages, candidates are now fully utilizing

everything social media has to offer.

Saturday, April 9, 2016

The Narrative Truth of Digital Hyperfiction: "Lies" and "Alter Ego"

I spent quite a bit of time navigating through Rick Pryll’s

“Lies” this week. From the first click, I was charmed—the simple formatting,

the brief narrative glimpses, even the two-fold “Truth” and “Lies” buttons

staring through the screen—these were all aspects of Pryll’s hyperfiction short

story meant to draw readers in.

I could not settle for a single read-through, but the first

time, I did continuously click “Truth” until the end. I want to believe that my

selection reveals something about my character, but I just think a natural

reaction is to want the truth, especially from a work of literature. The

narrative surprised me, though, as I was awfully confused and didn’t quite

understand what the purpose was. Despite this reaction, I immediately went back

to the beginning and started over, this time selecting “Lies.”

What I found most fascinating is how the narrative was set

up in a way that required the reader to react. The information received for the

“Truth” was much different in certain areas than what was revealed for the

“Lies,” and the “Lies” sections seemed to provide the information that was

needed to make sense of the “Truth” sections. Knowing that the “summer lovers”

was actually just a code for the journals, and that the journals had these

personas, completely transformed the way that I was reading the story.

In regard to temporality, I think Pryll’s choice to create

this story in such a way is effective because it gives the reader the power of

progression. I could read and reread the story in several different ways. I

even alternated between the two choices, starting once with “Truth” first and

once with “Lies” first. Although these choices didn’t necessarily change how the narrative progressed

(considering it ends the same every time, or at least it did for the decisions

I made throughout the story), I still felt like my conscious decision to click

either button might effect the next page.

Pryll’s “Lies” reminded me of Dr. Peter J. Favaro’s game

“Alter Ego,” which reads very much like a story. Unlike Pryll’s “Lies,”

however, it takes the reader from infancy to death, providing a variety of

choices for the user to select in order to progress the narrative.

These two stories are not similar just because of the plain

interface and reader-text interaction capabilities, but more so because every

choice results in a change in the narrative. In “Lies,” the next few sentences

of the text are formulated based on the reader’s decision. In “Alter Ego,”

readers are faced with the same kind of decisions, although the outcomes are

much more broad, and the choices the reader/user makes are carried throughout

the entire narrative from infancy until death, whenever that may be.

For example, as a baby, the reader peers into the mirror,

and by choosing to recognize him or herself as a “beautiful baby,” self-esteem

and awareness is then increased. Those same qualities decline if the reader

chooses to disidentify with the baby in the mirror. Ultimately, the reader must

piece together this puzzle of life by using their own decision-making skills to

progress the story.

What is most interesting, however, is how both of the texts

use these decision-making features to give the reader full control of time.

With a book, readers are able to jump around and pick and choose what they want

to read. Even in a novel, readers might be tempted to head to the end of the

book to see what happens, or even skip over paragraphs or chapters if they are

bored.

With interactive texts like these, there is much more at

stake. The reader is no longer given the freedom to bounce around the narrative,

but instead must carefully read each selection of text if they want to make an

informed decision and move themselves forward. In “Lies,” one could easily

click through the slides at a quick rate, but the entire story is then at

stake. The user sees these decisions being made (irrationally, perhaps?) and

when they arrive at the end, nothing is left but a tiny bit of text. They

cannot flip back a couple of pages. They must start all over again.

The same interaction works with “Alter Ego.” Whenever I used

to play the game in high school, I remember being upset with certain decisions

I had made, so I would try and refresh the page or click the backward arrow,

which would do nothing but mess up the game. There was no way to change those

decisions unless I started over, which, for the most part, was not only

inconvenient, but also defeated the purpose of the game—I needed to follow

through to find out what the point was.

By controlling the rate in which the narrative develops,

readers have the chance to feel like the story is more intertwined with them as

opposed to a standard book. These

stories also layer the narrative in ways that defy the standards of a literary

text—every action has a reaction—and the reader, with all their power and

glory, finally gets to be in charge of those actions.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)